Вашему вниманию предлагается перепост, из возможных неудобств - английский язык. Здесь можно узнать как появился стандарт ATLS, пульсоксиметрия при наркозе, электронный мониторинг плода (FHR) и многое другое. Какие события этому предшествовали.

We learn most fr om our painful mistakes. Mistakes can injure patients and land physicians in legal and professional trouble. Studying these mistakes and learning how to prevent, monitor, and respond to them, however, has changed the standards of care. By working to eliminate common medical errors, physicians can protect patients, protect themselves from lawsuits, and help lower the cost of their professional liability insurance premiums.

In 1910, when Abraham Flexner researched the state of US medical education, only 16 of the existing 155 medical schools required more than a high school education for admission. Germ theory was still disputed.

The practice of medicine in the United States is now much more standardized, thanks in large part to changes to standardization of the qualifying examinations for US-trained physicians and to medical malpractice law.

Today's standards of care are now mostly based on scientific evidence. In the past 20 years, courts have held physicians and hospitals to national standards of care rather than accepting local variations in the practice of medicine.

In 1976, Dr. Jim Styner, an orthopedic surgeon, crashed his small plane into a cornfield in Nebraska, sustaining serious injuries. His wife was killed, and 3 of their 4 children were critically injured. At the local hospital, the care that he and his children received was inadequate, even by standards in those days. "When I can provide better care in the field with lim ited resources than what my children and I received at the primary care facility, there is something wrong with the system, and the system has to be changed," Dr. Styner said.

His family's tragedy and the medical mistakes that followed gave birth to Advanced Trauma Life Support (ATLS) and changed the standard of care in the first hour after trauma.

Dr. Styner helped produce the initial ATLS course. In 1980, the American College of Surgeons Committee on Trauma adopted ATLS and began disseminating the course worldwide. It has become the standard for trauma care in US emergency departments and advanced paramedical services. The Society of Trauma Nurses and National Association of Emergency Medical Technicians have developed similar programs based on ATLS.

Judy was 39 years old when she went to the hospital for a hysterectomy. After she died on the operating table, autopsy revealed that the anesthesiologist had placed the endotracheal tube in her esophagus, not her trachea.

Today, anesthesiologists measure a patient's carbon dioxide levels -- which are much higher from the trachea than from the esophagus -- through use of an end-tidal carbon dioxide monitor.

In 1982, ABC's 20/20 ran a segment titled "The Deep Sleep: 6000 Will Die or Suffer Brain Damage." This program highlighted several cases of medical mishaps that resulted in serious injury or death. The American Society of Anesthesiologists responded with a program to standardize anesthesia care and patient monitoring and in 1985 created the Anesthesia Patient Safety Foundation.

Standard practices now include the use of pulse oximetry and end-tidal carbon dioxide monitoring for anesthetized patients. The new standards have markedly reduced the frequency of anoxic brain injury and other major complications. The push for electronic monitoring systems for patients under anesthesia caused anesthesia-related deaths to plummet from about 1 in 10,000 to 1 in 200,000 in less than 2 years.

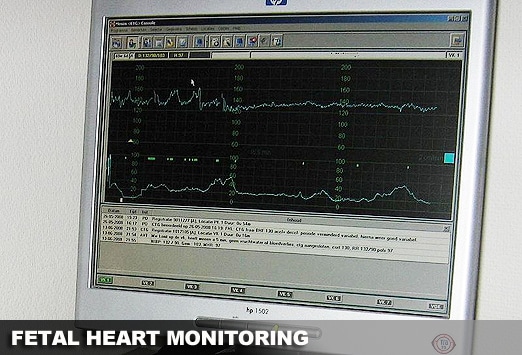

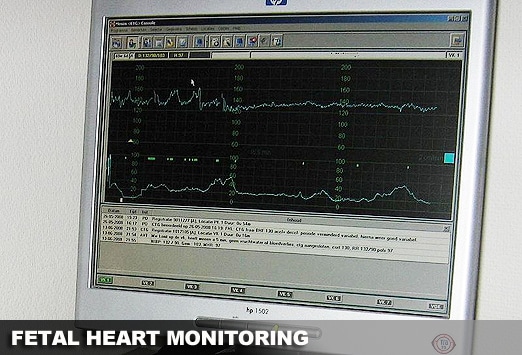

Sally and Ed looked forward to the birth of their first child. Sally's labor was long, so her obstetrician added oxytocin to speed things up. Unfortunately, administration of oxytocin led to unrecognized fetal distress, and their newborn daughter suffered severe brain injury and cerebral palsy.

Fetal monitoring to test both uterine contractions and fetal heart rate (FHR) is now the standard of care, with a 30-minute response time from recognition of fetal distress to delivery. The purpose of FHR monitoring is to follow the status of the fetus during labor so that clinicians can intervene if there is evidence of fetal distress, as reflected by an FHR above or below the normal range of 110-160 beats/min or an FHR that does not change in response to uterine contractions.

Electronic fetal monitoring (EFM), also called FHR monitoring, was first developed in the 1960s. Since 1980, the use of EFM has grown dramatically, from being used on 45% of pregnant women in labor to 85% in 2002, according to the American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG). "When EFM is used during labor, the nurse or physicians should review it frequently," state ACOG guidelines.

Bill had a seizure and crashed his car into a tree, crushing both legs. Arteriography revealed that his right leg was salvageable but his left leg was not. Unfortunately, the x-ray technician mislabeled the films, mixing left for right, and the orthopedic surgeon first amputated Bill's right leg.

Preventing wrong-site surgery became one of the main safety goals of the Joint Commission for Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations (JCAHO). Establishing protocols became an accreditation requirement for hospitals, ambulatory surgery centers, and office-based surgery sites.

JCAHO mandates standardization of preoperative procedures to verify that the correct surgery is performed on the correct patient and at the correct site. Guidelines include marking the surgical site, involving the patient in the marking process, and having all members of the surgical team double-check information in the operating room.

Despite these efforts, wrong-site surgery occurs about 40 times a week nationwide, a JCAHO survey found. The biggest pitfall is inadequate information about the patient. The solution is a carefully standardized method of collecting information.

Часть II

Источник

We learn most fr om our painful mistakes. Mistakes can injure patients and land physicians in legal and professional trouble. Studying these mistakes and learning how to prevent, monitor, and respond to them, however, has changed the standards of care. By working to eliminate common medical errors, physicians can protect patients, protect themselves from lawsuits, and help lower the cost of their professional liability insurance premiums.

In 1910, when Abraham Flexner researched the state of US medical education, only 16 of the existing 155 medical schools required more than a high school education for admission. Germ theory was still disputed.

The practice of medicine in the United States is now much more standardized, thanks in large part to changes to standardization of the qualifying examinations for US-trained physicians and to medical malpractice law.

Today's standards of care are now mostly based on scientific evidence. In the past 20 years, courts have held physicians and hospitals to national standards of care rather than accepting local variations in the practice of medicine.

In 1976, Dr. Jim Styner, an orthopedic surgeon, crashed his small plane into a cornfield in Nebraska, sustaining serious injuries. His wife was killed, and 3 of their 4 children were critically injured. At the local hospital, the care that he and his children received was inadequate, even by standards in those days. "When I can provide better care in the field with lim ited resources than what my children and I received at the primary care facility, there is something wrong with the system, and the system has to be changed," Dr. Styner said.

His family's tragedy and the medical mistakes that followed gave birth to Advanced Trauma Life Support (ATLS) and changed the standard of care in the first hour after trauma.

Dr. Styner helped produce the initial ATLS course. In 1980, the American College of Surgeons Committee on Trauma adopted ATLS and began disseminating the course worldwide. It has become the standard for trauma care in US emergency departments and advanced paramedical services. The Society of Trauma Nurses and National Association of Emergency Medical Technicians have developed similar programs based on ATLS.

Judy was 39 years old when she went to the hospital for a hysterectomy. After she died on the operating table, autopsy revealed that the anesthesiologist had placed the endotracheal tube in her esophagus, not her trachea.

Today, anesthesiologists measure a patient's carbon dioxide levels -- which are much higher from the trachea than from the esophagus -- through use of an end-tidal carbon dioxide monitor.

In 1982, ABC's 20/20 ran a segment titled "The Deep Sleep: 6000 Will Die or Suffer Brain Damage." This program highlighted several cases of medical mishaps that resulted in serious injury or death. The American Society of Anesthesiologists responded with a program to standardize anesthesia care and patient monitoring and in 1985 created the Anesthesia Patient Safety Foundation.

Standard practices now include the use of pulse oximetry and end-tidal carbon dioxide monitoring for anesthetized patients. The new standards have markedly reduced the frequency of anoxic brain injury and other major complications. The push for electronic monitoring systems for patients under anesthesia caused anesthesia-related deaths to plummet from about 1 in 10,000 to 1 in 200,000 in less than 2 years.

Sally and Ed looked forward to the birth of their first child. Sally's labor was long, so her obstetrician added oxytocin to speed things up. Unfortunately, administration of oxytocin led to unrecognized fetal distress, and their newborn daughter suffered severe brain injury and cerebral palsy.

Fetal monitoring to test both uterine contractions and fetal heart rate (FHR) is now the standard of care, with a 30-minute response time from recognition of fetal distress to delivery. The purpose of FHR monitoring is to follow the status of the fetus during labor so that clinicians can intervene if there is evidence of fetal distress, as reflected by an FHR above or below the normal range of 110-160 beats/min or an FHR that does not change in response to uterine contractions.

Electronic fetal monitoring (EFM), also called FHR monitoring, was first developed in the 1960s. Since 1980, the use of EFM has grown dramatically, from being used on 45% of pregnant women in labor to 85% in 2002, according to the American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG). "When EFM is used during labor, the nurse or physicians should review it frequently," state ACOG guidelines.

Bill had a seizure and crashed his car into a tree, crushing both legs. Arteriography revealed that his right leg was salvageable but his left leg was not. Unfortunately, the x-ray technician mislabeled the films, mixing left for right, and the orthopedic surgeon first amputated Bill's right leg.

Preventing wrong-site surgery became one of the main safety goals of the Joint Commission for Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations (JCAHO). Establishing protocols became an accreditation requirement for hospitals, ambulatory surgery centers, and office-based surgery sites.

JCAHO mandates standardization of preoperative procedures to verify that the correct surgery is performed on the correct patient and at the correct site. Guidelines include marking the surgical site, involving the patient in the marking process, and having all members of the surgical team double-check information in the operating room.

Despite these efforts, wrong-site surgery occurs about 40 times a week nationwide, a JCAHO survey found. The biggest pitfall is inadequate information about the patient. The solution is a carefully standardized method of collecting information.

Часть II

Источник

Комментарии (0)